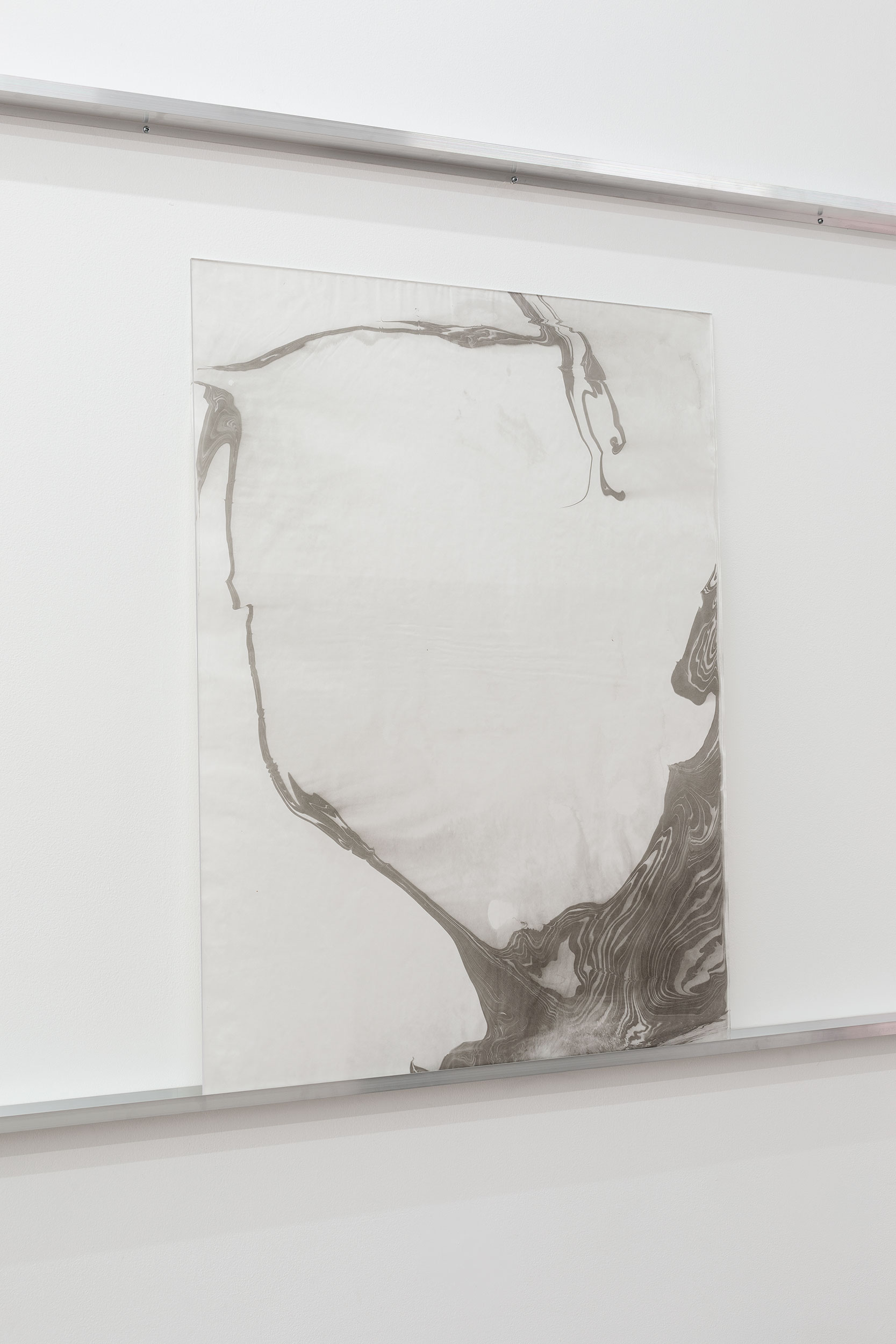

Gertrude Glasshouse, Melbourne (2020)

Solo Exhibition

(Photography: Christian Capurro)

Conversation with Peter Wiltshire, Senior Ranger at Darebin Parklands, recorded on-site, 18.2.2020.

Conversation with Peter Wiltshire, Senior Ranger at Darebin Parklands, recorded on-site, 18.2.2020.

JG: Can you start by giving a brief history of this site from its geological formation through to its urban transformation?

PW: The geology of the parklands differs on either side of the Darebin Creek. It’s Silurian sandstone on the Ivanhoe side and on this side its quaternary basalt - around 860,000 years old. It’s the youngest basalt in Victoria. We sit on a fracture point where the lava flow came across and met a body of water and cooled down rapidly; so you had these fracture points in the basalt and over time humans discovered they could quarry it. For thirty-thousand years the Wurundjeri people cared for this land and farmed this land, though it wasn’t recognised. European settlement comes in and instantly the land is used for market gardens to grow foods, citrus crops, mulberry trees, quince trees, also dairy farming. Then it was recognised that it would useful to extract the rock as a resource and became a quarry, then a tip, and what are you going to do with an old landfill? You can’t build on it, well you can but its very expensive, so the local residents recognised the beauty of the creek area and lobbied for it to become a public park. Most people who come to the parklands don’t realise this history, that it was landfill, they think it’s a natural bushland park, a little oasis.

JG: This is a common story among public parks around the northern suburbs, many of which were quarries and later landfill tips. Its like they were returned to the public as a last resort, once all other value had been extracted from them?

PW: They took 6 million tonnes of rock out of this quarry over 70 years from 1890 through to 1960. Some of it was bluestone, and some was crushed into blue-metal (used to pave roads) and ballast (used along railway tracks) and of course the bluestone itself was used for curb and channel and construction of buildings such as churches and civic buildings around Melbourne. In the mid 60s when the all the useful stone was removed, Northcote council realised they could fill this huge hole with landfill. So it was opened up as a landfill in 1968 and by 1974 it was full! What took 70 years to excavate, took only 6 years to fill with rubbish.

JG: That is an alarming rate of metabolism! Its hard to imagine all that stone transposed across the Melbourne landscape to pave the city… and the sheer rate of consumption and waste the city produces! Can you describe what ‘leachate’ is and how it flows through this narrative? Why is it here and where does it come from?

PW: The watertable running into the tip-site creates leachate. The quarry was dug down 65 meters, but even at 14 meters deep, water from a local aquifer started pouring into the site, which eventually formed a lake in the bottom of the quarry. They used to pump that water into the Darebin Creek. Jumping forward, when they fill the quarry up with rubbish, that water still comes in. Water’s a great solvent so it can start ripping things apart and mixing with them. 8 years after the tip closed, a black ooze started coming out of the side of the slope on the eastern wall. Residents noticed it flowing straight into the creek and they took samples of it to the EPA, and the EPA came down and said, “Yeah you’ve got a leachate problem”. At that point the leachate was flowing through that tip-site at a rate of half a million litres every seven days! So they had to do something massive to deal with that volume. The council eventually built this treatment system to contain the leachate and improve the quality of it. And it was 46% ammonium, so it’s not like drinking water or something, its toxic to everything.

JG: I’m imagining this complex chemistry as a record of human intervention oozing from the site. Is it possible to trace the chemicals back to through time like a geaneaolgy of local businesses and industries that used the site for their waste?

PW: Easily done. A good example is that we have high levels of potassium-chloride, which comes from saltpetre used as a preservative in the meat industry, because the local abattoirs deposited all their waste here. We’ve also got high levels of bromine and boron, other chemicals that are used in the photographic industry and we know from records that the photographic-plant at Coburg used to bring some of their waste here. The other is of course the industrial inks, tannins and dyes that were used to manufacture paper at the mills just up the road here. The tip was licensed for domestic waste, which is a pretty ambiguous statement, but the real issue was how it was monitored… The EPA wasn’t formed until 1972, so the monitoring of what went into landfill was up to the council itself. Let me draw you a picture of that: You’ve got some guy who’s twisted his back shovelling or something, so they’ve stuck him on the front gate and said “tell people where to dump their waste”. So what happens is someone comes down and offers him a bottle of Jack Daniels – it just so happens they’ve got nuclear waste – he says “yeah no worries mate, stick that down that back corner there, that should be deep enough and out of the way”… So the sort of stuff that went into this landfill site is continually causing issues now, and that’s what I’m here for.

JG: Can you explain how your leachate treatment system works?

PW: First and foremost its major function is to stop any leachate getting into Darebin Creek. So it’s a containment system first and foremost, and is successful at that. Then we collect the water and pump it into a network of wetlands and biological filters to improve the quality of the water. And we get it to the point where we have a successful ecology living in the lower ponds. The treatment phases break down the toxic elements like ammonium, down to ammonia… then heavy metals are trapped in the sediment ponds we’ve built and all the nitrogen-based nutrients such as the nitrates and nitrites are used by plants in the biological filter.

JG: How do these processes interact with groundwater flows and the water-cycle more broadly?

PW: Yeah, very much so! The aquifer that supplies the leachate system, is an open aquifer so it is charged by water landing on the ground, settling down through the surfaces, getting caught and channelled through the ground and eventually leaking into our system. So it’s a dynamic thing! An open system is dynamic because the flow itself creates erosion, which creates movement underground. What do they call this period ‘The Anthropocene’? Our effect on the subterranean water is unbelievable! We’re effecting the aquifers, we extract water out of them, but more crucially in this case we’re stopping the regeneration of aquifers because we’re building hard surfaces everywhere and pushing all the rainwater into creeks through stormwater drains and not allowing it absorb into the ground. So long term, what happens when the aquifers dry up? That’s the question! It can’t be a good thing to let the aquifers run dry underneath your cities… you were talking about the metabolism of cities; I’d say aquifers are a key component of that metabolism.

JG: Most of us don’t realise the constant movement of water beneath our feet, that we have aquifers flowing underground even in urban areas; and how toxic they can become. How do you think these flows will continue here, into the future?

PW: It’s a huge question. The parklands is now very valuable to the community, but at the same time it’s put under tremendous pressure, because everyone wants a piece of it. And its only going to get more popular as Melbourne’s population increases and these open space areas become more and more precious. The leachate system is an interesting one… I’ve always said it will become very saline, the salts will concentrate to such a point that the lakes will become home to extremophiles; we’re talking about bacteria and algae that live in salt-flats, that’s what will happen if we keep going the way we’re going now. But if we divert storm-water into the system and invest in that, we could dilute it back to an almost freshwater system in the next 50 years. There will always be leachate here unless the aquifer suddenly decides to start flowing in another direction, for 150 years at least. But if we add stormwater into the system we could clean it right up, which is our number one target. But the local government has to be willing to do it. They have to decide if the investment is worth it to them? They could have a network of pink lakes in 150 years with a couple of flamingos on it, or they could have a beautiful aquatic eco-system that everyone will enjoy.